Documentary Marking 50 Years Since Nigeria-Biafra War Launches In London

Dr Louisa Egbunike’s documentary weaves together an engaging narrative of reflections from authors touched by one of the most devastating conflicts of the 1960s, one that still casts its shadow on Nigerians around the world

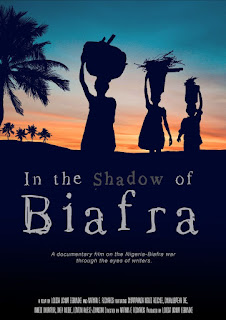

On Saturday 25th January 2020, a sold-out Curzon Bloomsbury cinema played host to the launch of In The Shadow of Biafra, a documentary reflecting on 50 years since the end of the Nigeria-Biafra War.

Produced by Dr Louisa Egbunike from City, University of London’s Department of English, and directed by filmmaker and University of Sussex PhD student Nathan Richards, the film juxtaposes a variety of reflections by creative writers – both those who lived through the war, and those who have been touched by its impact on their families both before and since they were born.

The film engages with topics such as how the war is remembered, the inheritance of trauma and the role of writers during the war.

The film includes interviews with writers including Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Inua Ellams, Ernest Emenyonu, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Okey Ndibe, Obi Nwakanma, Nnedi Okorafor, Tochi Onyebuchi, Data Phido, and the late Chukwuemeka Ike, who sadly passed away on 8th January 2020 and who receives a dedication at the end of the film.

Attendees at the launch included: Professor Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo, the respected Nigerian author and University of Lagos academic who also features prominently in the film [first photo below]; Chi-chi Nwanoku OBE, founder of Chineke!, Europe's first majority BAME orchestra [second photo]; and Chibundu Onuzo, author of The Spider King's Daughter [third photo].

After the film concluded to enthusiastic applause from the audience, Dr Egbunike and Richards took part in a Q&A session, chaired by Sarah Ozo-Irabor, presenter of the Books & Rhymes podcast.

In response to a question about the contrasting opinions aired in the film, Richards said: “There were a lot of tensions, which we put side-by-side.”

Dr Egbunike added: “There end up being interesting conversations between people in the film [due to how comments are woven together].”

But as filmmakers, how did they deal with these contradictions in the narrative?

“The point is to not try to resolve the contradictions in what people say; instead, out of those contradictions comes a conversation,” said Dr Egbunike.

“By putting different interpretations alongside each other, in our way we are trying to contribute to the conversation.”

Richards concurred, saying: “We weren’t doing a history. We were engaging with memory – because that’s one way in which people deal with trauma.”

The story of Biafra

When people conjure up images of war in the late 1960s, Vietnam tends to come immediately to mind. But there was another war happening in West Africa at this time – the Nigeria-Biafra War.

The divisions in Nigeria had their roots in British colonial divide-and-rule policies. And when Nigeria gained its independence in 1960 there were inherent tensions in the politics of that space during the years that followed.

Tensions escalated and in 1966 – after a coup and counter-coup – Igbo people living in northern Nigeria were targeted and killed. Survivors left the north and fled to their home towns in the Eastern region.

After a series of failed negotiations, those in Biafra felt unsafe in Nigeria and Biafra subsequently declared its independence. In 1967, a war between Biafra and Nigeria began.

In a recent segment for The Guardian’s Today In Focus podcast, Dr Egbunike described the situation in Nigeria at that time.

“The British, being the former colonisers, wanted to maintain what they’d created – in part because the borders of Biafra included the region of Nigeria that had oil wells,” she said. “So, Britain backed Nigeria in the war and provided the Nigerians with arms.

“But increasingly, as the media presented images of children starving – the hopelessness, the refugees, the displaced people – the British public had great sympathy for the Biafrans, donating money for the Biafran cause and putting pressure on the British government.

Famously around this time, The Beatles’ John Lennon handed back his MBE, in his words “as a protest against violence and war – especially Britain’s involvement in Biafra”. The conflict also directly led to the formation of Médecins Sans Frontières.

British pressure

The British government was under pressure because the general public didn’t agree with its stance. Consequently, Britain in turn put pressure on Nigeria and didn’t want the war to continue to be drawn out. That, in turn, meant they needed to win the war quickly.

“Biafra had lost a lot of territory; there were blockades in place so it was difficult for aid to get in,” said Dr Egbunike. “People couldn’t maintain their farms and so there was no way of feeding Biafrans within Biafra. People were starving.

“And then the military attacks were not just on Biafran soldiers, they deliberately targeted civilians.

“After almost three years, the War ended in January 1970. Those who were living in Biafra had their Nigerian bank accounts emptied and were given £20.

“The focus was on ‘how do we rebuild?’,” said Dr Egbunike. “And people did, but the flip-side of that was that the trauma people felt got buried, there was never a space to reckon with that trauma. Nigeria hasn’t reckoned with its history.

“Many parents and grandparents aren’t telling their children about the war. There hasn’t been a fully formed, developed notion of a national identity. There are still tensions along ethnic lines.

“When it comes to Biafra, part of the reason why there hasn’t been a public conversation is because those in power don’t necessarily want that conversation.

“Many people who were part of that war, don’t want to reckon with that history.”

Dr Egbunike is currently in the process of scheduling further screenings for In The Shadow of Biafra, with a second film also in the pipeline. For updates, follow @ShadowOfBiafra on Twitter.

Comments