‘Gone Like A Meteor’: Epitaph For The Lost Youth Of The Biafran War

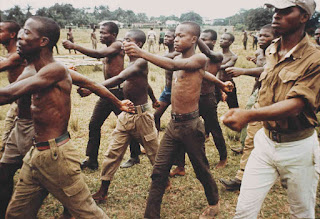

Young men training for the Biafran War. Image: Rolls Press Popper foto/Getty, August 1968

In 1967, Nigeria had been an independent country for just seven years. The declaration of secession that year by an Igbo majority in the southeastern region of Nigeria, and the war that followed when the federal government decided to keep the country as one, was already the culmination of a bloody sequence of events. By May 1967, two coup d’états had taken place, and the Igbos of northern Nigeria had been killed in the tens of thousands.

The Biafran War, otherwise known as the Nigerian Civil War, lasted from July 6, 1967, until January 15, 1970. The men who led each side—Yakubu Gowon on the federal side and Chukwuemeka Ojukwu of Biafra—were in their mid-thirties. Boys, some barely teenagers, volunteered to fight for the breakaway Republic of Biafra. Many of the civilian casualties were children: in September 1968, the International Committee of the Red Cross estimated that almost ten thousand people died daily from starvation caused by Nigeria’s blockade of Biafra. An entire generation was wrenched from the future.

My uncle was part of that generation. He couldn’t have been older than twenty-five when he enlisted in the Biafran army. He went to the front around the beginning of the war and never returned. My family always assumed that he had been killed close to the end of the war, but we never knew this for sure. In part because I was named after him, when I hit my mid-twenties I began to wonder about the promise his life once held. His afterlife—as a specter, as one who lives only in our memories of him—still interests me. What was the meaning of his life, if he died so young and left nothing behind?

In 1971, the late Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe published a volume of poems that addressed the trauma of that time, albeit obliquely. He later reflected on these works: “There is some connection between the particular distress of war, the particular tension of war, and the kind of literary response it inspires. I chose to express myself in that period through poetry, as opposed to other genres.” His memoir, There Was a Country, is a compendium of personal and historical facts, and while he does include some poems, when he turns to prose his sentences are written with restraint, without imaginative flourishes. Before its publication in 2012, Achebe had addressed the war mainly through those poems. Perhaps when he tried to tell a story and sensed afresh the horror, he stood up from his desk, shut the door, and never wrote a word for months.

The books published about the war, by memoirists on either side, are written from the perspective of those who survived, and can manage to speak of its horrors. The dead, voiceless, keep to themselves. And what of the unborn? When I remember my uncle, it is to grieve for a man whom I never knew, forty years after his death.

Christopher Okigbo, a poet, and the Time-LIFE photographer Priya Ramrakha both died in the Biafran War. The men never met each other but shared a setting for what would be the final labor of their lives. Like my uncle, they, too, died young: one at thirty-four, the other at thirty-three.

Ramrakha had taken photographs of conflict zones all over the world—dead Mau Mau fighters in Kenya, mourners after a riot in Djibouti, casualties of a British attack in Aden—but his obituary in LIFE noted that “he regarded the war between Nigeria and secessionist Biafra as his own.”

For his part, Okigbo, who had studied classics in university and once taught Latin, decided on a course of action that seemed uncharacteristically anti-intellectual. The best use of his genius wouldn’t be to serve Biafra as a roving ambassador like Achebe, or to work creatively, composing poems or anthems, or designing propaganda posters as the artist Uche Okeke did. In those desperate days, options were limited and the utopian claims of the Biafran Republic seemed non-negotiable—at least for those with an idealistic sense of duty like Okigbo. He joined the Biafran Army as a field-commissioned major, something he had gone to great lengths to keep from his family and friends, including Achebe.

“That’s my work, duty calls, so I must go there,” Ramrakha said, according to his brother, when asked why he went to places like Aden. Okigbo must have had a similar sentiment.

I wondered about the relationship between the two men and their era when I noticed similarities in a pair of poems. The first is a stanza from Osip Mandelstam’s poem “The Century”:

My century, my beast, who will manage

to look inside your eyes

and weld together with his own blood

the vertebrae of two centuries.

In 1971, Okigbo’s posthumous collection, Labyrinths with Path of Thunder, was first published, and included the poem, “Elegy of the Wind,” in which he wrote:

White light, receive me your sojourner; O Milky Way,

let me clasp you to my waist;

And may my muted tones of twilight

Break your iron gate, the burden of several centuries,

into twin tremulous cotyledons…

One poet wonders about the welding together of two centuries. The other hopes that the burden of several centuries might be broken apart. Okigbo’s conversation with Mandelstam, as I see it, is not necessarily about how their centuries might be approached. They are conversing, instead, about the ways an individual life fits within a span of time: a person can “look inside” the eyes of two centuries much as his “muted tones of twilight” can break its iron gate.

In his essay “What is the Contemporary?” (2009), the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben investigates the nature of time in Mandelstam’s poem. “Those who are truly contemporary,” he writes, “who truly belong to their time, are those who neither perfectly coincide with it nor adjust themselves to its demands. They are thus in this sense irrelevant. But precisely because of this condition, precisely through this disconnection and this anachronism, they are more capable of perceiving and grasping their own time.”

What if a poet were so within his own epoch that he could also claim to be outside of it? “The contemporary,” Agamben continues, “is he who firmly holds his gaze on his own time so as to perceive not its light, but rather its darkness. All eras, for those who experience contemporariness, are obscure. The contemporary is precisely the person who knows how to see this obscurity, who is able to write by dipping his pen in the obscurity of the present.”

The last time Chinua Achebe saw Okigbo was in the second month of the war. Achebe’s apartment in Enugu—then the capital of the fledgling Republic of Biafra—had just been bombed. He remembers Okigbo wearing a white gown and cream trousers, milling around the destroyed apartment among a vast crowd of sympathizers who wanted to commiserate with the novelist.

“So I hardly caught more than a glimpse of him in that crowd,” Achebe wrote in There Was a Country, “and then he was gone like a meteor, forever. That elusive impression is the one that lingers out of so many. As a matter of fact, he and I had talked for two solid hours that very morning. But in retrospect that earlier meeting seems to belong to another time.”

Gone like a meteor, forever. Death as the extinguishing of light. The quickness and suddenness and permanence of it, how unexpected it was—not as in the gradual dimming of the afternoon sun, but rather the darkness that results from flicking a switch.

In August 1967, just weeks after Achebe’s last encounter with him, Okigbo was killed in a conflict near the university town of Nsukka. In the final stanzas of “Elegy for Alto,” Okigbo had written:

Earth, unbind me; let me be the prodigal; let this be

the ram’s ultimate prayer to the tether…

An old star departs, leaves us here on the shore

Gazing heavenward for a new star approaching;

The new star appears, foreshadows its going

Before a going and coming that goes forever…

He seemed to predict his own death—like a star taken from the sky—in the poem. All his life, Okigbo appeared to live in the confident expectation that he could realize any ambition, could dabble in anything he thought worthy. He co-founded a publishing house, became a librarian despite having no training, and when it was time to defend the university town he’d worked in, he became a soldier. His bravado led to an early death. His whole life, it seems, he had been preparing to become a myth.

By the time his collection, Labryinths, was published in 1965, his thinking was already marked by a mingled sense of mourning and a desire for something less temporary, even existential—he introduced the book as “a fable of man’s perennial quest for fulfillment.”

His poems conjure the image of a destructive war, yes, but he also wrested from the violence of that decade clear and rallying metaphors. Thunder, for instance, recurs in the title of his poems—“Thunder can Break,” “Come Thunder,” “Hurrah for Thunder.” “Thunder has spoken / Left no signatures: broken,” he writes, as if to emphasize the sudden rumbling of a destructive, violent force.

What can be done with knowledgeable presage of a broken world, when, as Okigbo writes in “Come Thunder,” “the smell of blood already floats in the lavender-mist of the afternoon,” and “a great fearful thing already tugs at the cables of the open air?” In “Thunder can Break,” he seems to respond:

Bring them out we say, bring them out

Faces and hands and feet,

The stories behind the myth, the plot

Which the ritual enacts.

On October 2, 1968, a Nigerian major invited a group of journalists—Ramrakha, CBS correspondent Morley Safer, and Walter Partington of the London Daily Express—to walk with him to the top of a hill four miles outside Owerri. When Partington looked toward the top of the hill, he noticed two soldiers. The major insisted they were under his command. This was not the case. They had been ambushed. The journalists dodged out of sight as the Biafran soldiers opened fire.

There was a trench dug in the road between the ambushed men and the top of the hill. Partington saw Ramrakha twenty yards away, moving from cover, holding his 300-mm Nikon camera. Ramrakha’s last photographs document these final moments. Two soldiers inch forward, one crouching as he readies his rifle. In the background is a narrow and hilly road bordered by dense trees: the loneliness of the scene, the absent yet omnipresent enemy, the tension in the faces of men look not as if they have made a pact with danger, but with survival.

They all heard him scream, “I’m hit!” The range from which he was shot—the bullet struck him in the right shoulder and passed through his body—couldn’t have been more than seven yards, Partington reported in his dispatch.

Ramrakha died an hour later. A Nigerian officer carried his body from the road. In the commentary Safer made for that night’s TV news broadcast, he said: “He possibly could have been saved, but the medical care is so rudimentary he had to die. This is Morley Safer, CBS News in Owerri, a place barely known and quickly forgotten.”

Safer’s idea is perhaps to condemn the place to forgetfulness so that Ramrakha can remain unforgotten. CBS footage of the dying photographer that survives from that afternoon show him with flailing hands as Safer crawls toward him, grabbing Ramrakha by the legs. Later, when the photographer is on a stretcher, his eyes are closed and his lips slightly parted. (Stills of these scenes are included in a new monograph documenting Ramrakha’s life, edited by Shravan Vidyarthi and Erin Haney.)

Most telling is how close he gets to the Biafran soldier who took his life. He might have been blinded by bravado, or perhaps he mistook youth for invincibility. None of these claims are as important as the fact that he got close and he kept his shutter working.

Ramrakha—born in Kenya to an Indian consular official, the grandson of a stationmaster on the railway from Mombasa to Nairobi—took some of his earliest photographs as a teenager. Paul Theroux, whom Ramrakha met in Uganda, tells of how they had come across a large, dead snake. Ramrakha didn’t take a photograph, recounts Theroux, but paced around it, examining it through his viewfinder, as if studying it. A man’s light, his ways of seeing, of being in the world: this happened for him through the camera.

In the foreground of one of Ramrakha’s photographs from the Biafran War, bodies in repose are laid out with their faces to the ground, or skywards, or sideways, totaling almost two dozen. Each is marked by the aftermath of fire. Flesh is charred and cloth is blackened. It is quite likely they have been laid out for identification. In the background are the living, standing or in motion, walking towards, edging away. One man in a red shirt sits close to the pillar of what is built as a school block, a hand on his knee. Of everyone pictured alive, his pose best denotes survival, the one who witnessed others die.

Another of his photographs was printed in LIFE with the following caption: “Outside a bombed-out house in the village of Owerri, a weeping mother tells neighbors she is giving up hope of ever finding her daughter alive. The girl, seven, who had panicked at the sound of the planes, fled from her house and disappeared into the forest.”

There is a category of sorrow best regarded from a distance. Watching all three women, their lips pursed, I note the bridge between mourner and onlooker. Right there, in the woman’s hands, clasped tenderly around her neighbor’s ribcage as if to suture a gashing sob, those downcast eyes that wouldn’t reach yours, those faces only known from the side.

Youth is a meteor, gone in a flash. The tragedy of the deaths of Okigbo and Ramrakha is outbalanced by the longevity of their words and pictures. They survive through what they managed to wrest from the terrible war. My uncle wasn’t as fortunate. The details of his life are vague and imprecise, amounting to no more than an hour of talk when I sit with any relative.

One afternoon, I translated Christopher Okigbo’s middle name, “Ifekandu,” into these lines:

Something bigger than life,

Something better than life,

Something bigger and better than life,

This thing cannot be equated with life,

Life is too small in comparison,

Teach me to number my days, to apply my heart to something besides this life,

I have measured life and found it small in comparison,

Why speak of life in this world when you can speak of someplace better,

What is life compared to something vaster,

There is something better than life.

A friend soon pointed out to me that, in fact, I might be mistranslating. A person she knows, my friend said, also bore the name Ifekandu, and her family was from the same state in Nigeria as Okigbo. Whereas I’d translated “Ife” as “thing,” or “matter,” or “something,” my friend’s acquaintance said the word, in her name, meant “light.”

Priya Ramrakha: The Recovered Archive, edited by Erin Haney and Shravan Vidyarthi, is published by Kehrer Verlag.

SOURCE: THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

Comments